PROXIMITY: how much time do parent & child spend together, & to what extent is supervision practiced?

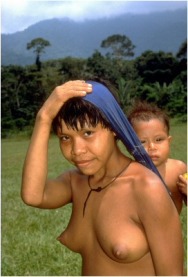

.Among the YANOMAMI, devoted care and protection of young ones is a top priority. This is because they are acutely aware of the vulnerability of their children(6). Incidence of disease is very high in the rainforest environment, and the weak immune systems of the children make them susceptible targets. The young are especially vulnerable to violent raids by outside groups, and have been known to be slaughtered in terrible massacres of innocents, causing extraordinary grief to their communties. Furthermore, according to Yanomami spiritual beliefs, supernatural evils pose a serious threat to poorly protected children. For these reasons, Yanomami parents, primarily mothers, keep their children of both sexes very close by and care for them tenderly throughout their early developmental years(7). As boys near puberty, they begin to spend more and more time with their fathers and other men for learning and maturation purposes, but are still looked after closely.

In JU'/HOANSI society, the degree of proximity between parents and children varies according to whether they are members of a sedentary or a nomadic community(8). Children in sedentary communities spend decidedly less time with their parents. The permanent village provides the stability and safety necessary for children to venture away from their homes and interact with others similar to them in age and sex, as opposed to staying at home under the watchful eye their mothers or other older female caretakers. The latter scenario is generally the case in nomadic Ju'/hoansi communities, for which constant movement and unpredictable circumstances make close supervision of children essential. In nomadic as well as sedentary communities, the father is less a part of his children's lives than the Yanomami father.

According to a 1984 study of suburban families in Onondaga County, New York, the suburban mother spent an average 3.5 hours per day in immediate proximity to at least one of her children, and the father spent an average of 2.0 hours per day with one or more children(9). Although this study predates the dawn of post-industrialism in the United States, the point holds true that parents in SUBURBAN AMERICA spend far less time in the presence of their children than their foraging counterparts. This can be attributed to two dominant factors. The first of these is the nature of the suburban dwelling place. The security of the house makes parental supervision of the child largely unnecessary once the child is of sufficient age to walk and entertain itself. Furthermore, the large size and compartmentalized structure of the house, in contrast to the one-room shelter in which most foraging families live, makes it possible for the parents and children to conduct different activities in different rooms, thus eliminating direct contact. The second factor is adult employment, the concept of which does not exist in the hunter-gatherer society. A fundamental feature of the post-industrial economy, adult employment in America draws in most cases the father, and often the mother, out of the home to work for significant amounts of time. While the parents are working, their children spend much of their time in school or daycare.

References:

6. Salamone 1997

7. Smole 1976

8. Barnard 1992

9. Bryant and Zick 1996

In JU'/HOANSI society, the degree of proximity between parents and children varies according to whether they are members of a sedentary or a nomadic community(8). Children in sedentary communities spend decidedly less time with their parents. The permanent village provides the stability and safety necessary for children to venture away from their homes and interact with others similar to them in age and sex, as opposed to staying at home under the watchful eye their mothers or other older female caretakers. The latter scenario is generally the case in nomadic Ju'/hoansi communities, for which constant movement and unpredictable circumstances make close supervision of children essential. In nomadic as well as sedentary communities, the father is less a part of his children's lives than the Yanomami father.

According to a 1984 study of suburban families in Onondaga County, New York, the suburban mother spent an average 3.5 hours per day in immediate proximity to at least one of her children, and the father spent an average of 2.0 hours per day with one or more children(9). Although this study predates the dawn of post-industrialism in the United States, the point holds true that parents in SUBURBAN AMERICA spend far less time in the presence of their children than their foraging counterparts. This can be attributed to two dominant factors. The first of these is the nature of the suburban dwelling place. The security of the house makes parental supervision of the child largely unnecessary once the child is of sufficient age to walk and entertain itself. Furthermore, the large size and compartmentalized structure of the house, in contrast to the one-room shelter in which most foraging families live, makes it possible for the parents and children to conduct different activities in different rooms, thus eliminating direct contact. The second factor is adult employment, the concept of which does not exist in the hunter-gatherer society. A fundamental feature of the post-industrial economy, adult employment in America draws in most cases the father, and often the mother, out of the home to work for significant amounts of time. While the parents are working, their children spend much of their time in school or daycare.

References:

6. Salamone 1997

7. Smole 1976

8. Barnard 1992

9. Bryant and Zick 1996